|

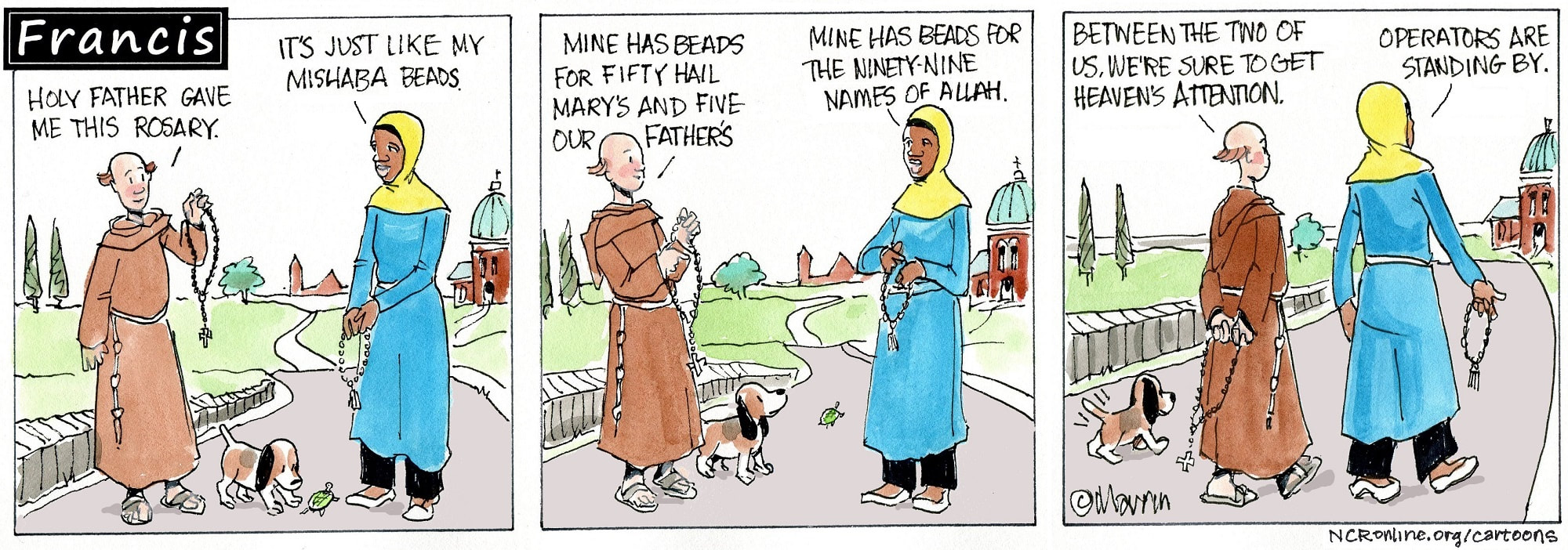

Tabernacle at Temple Beth Torah where God's Word is housed at Temple Beth Torah, Holliston, MA Reverend Bonnie Steinroeder, pastor of First Congregational Church in Holliston, Massachusetts, and I were recently invited to evening prayer services with our Jewish neighbors and friends at Temple Beth Torah for Yom Kippur. Our friendships were forged through close connections between the Christian churches in town and the local synagogue some years ago. Additionally, our interfaith dialogue project called the Metrowest Interfaith Dialogue Project began with these important relationships and widened the circle to include nearby faith leaders from other religious traditions including communities of Hindus, Sikhs, Bahai, Muslims, and the Spiritual but not Religious (SBNR). Kol Nidrei As a Christian that draws deeply from our Judaic roots, where the Hebrew Scriptures and the New Testament are received as one whole letter of love from God, the rhythm and cadence of the evening prayer of Yom Kippur resonated profoundly within me. As we walked into the prayer space with warm greetings from Rabbi Mimi Micner and members of the community, we began our prayer with Kol Nidrei. Rabbi Mimi and the Cantor wore white albs with their Tallitot or prayer shawls draped over them in what I perceived as anticipation of atonement and renewal for the whole congregation. I thought the declaration of Kol Nidrei to renounce past oaths to God was odd. But other commentators address this issue by saying that Kol Nidrei, in actuality, emphasizes the importance of keeping one’s word and reaffirms our belief in honoring our commitments. Numbers 15:26 is recited: “May all the people of Israel be forgiven, including all the strangers who live in their midst, for all the people are at fault.” How appropriate, as we enter a day when we will be saying over and over how we plan to change and do teshuvah, our return to God. As a gentile Catholic interfaith leader, I found as I stood with my Jewish neighbors, my own need to be forgiven by God, along with theirs, and how our healing is so inextricably tied together. Not just on a personal level, but in our interfaith ties and the ties we all share with humanity and the earth. Christianity’s history is darkly blemished by antisemitism, often citing our sacred texts for its justification. The Middle Ages saw the persecution of Jews following the outbreak of the Black Death in Europe in the 14th century by the Catholic Church. The Second Vatican Council in the 1960s saw improvements in the relationship following a repudiation of the Jewish deicide accusations and addressed the topic of antisemitism for the first time. Atonement can lead to new ways in our relationships. Shema, Listen During the Shema on Yom Kippur, the second line, Baruch Shem Kavod Malchuto LeOlam Va’ed, “Blessed is the Name of His Glorious Kingdom for all eternity” is read aloud. Moses originally heard this line from the angels when he was on Mount Sinai receiving the Torah from God. Though normally said quietly, on Yom Kippur it is said out loud. Normally, one dares not utter angelic phrases loudly, but on Yom Kippur, it is as if we are all spiritually raised to the level of angels, and we say the verse out loud. Courage is required! The Shema recounts the sixth chapter of Deuteronomy and the prayer that reverberates throughout other religious traditions, including Islam. “Hear O Israel, the Lord is our God, the Lord is One. Blessed is the name of His glorious Kingdom for all eternity. You shall love the Lord with all your heart, with all your soul, and with all your might. You shall teach them thoroughly to your children…” We all hold this enduring behest as Christians who also account for these same words through the lips of Jesus, with the addition from Leviticus, “and you shall love your neighbor as yourself.” (Matthew 22:37-39) Intergenerationally, across one hundred and twenty-six nations, through thousands of languages, through art, sacred texts, and enshrined in our secular cultures such as the Bill of Human Rights, we hold together, this all-encompassing command, perhaps even a plea. Listen to God, to each other, to the earth, to the cries of injustice, and to our need to celebrate our common humanity. Together we are a parable of God’s miracle each and every day if we choose to see each other as such. Our rich diversity of religious paths, each one a “sacrament” of God, profoundly shows that our religious diversity belies one interfaith voice, and the power of love that voice carries in a way our individual traditions cannot. The Contemporary Burden of Antisemitism There were other rich experiences in this evening’s prayer of Yom Kippur, but my attention was captured by the sermon of Rabbi Mimi and the burden of antisemitism. She spoke about how she often felt, in her younger days, that her Jewish community was alone, withstanding centuries of persecution without support or friends. It reminded me of the recent PBS film by Ken Burns and his collaborators, The US and the Holocaust. At best, this three-part series is profoundly disturbing in its truth of antisemitism, which was not only the product of Nazi politics but was also shored up by the unseen hand of Jewish prejudice outside of Europe, including the United States. As the program notes explain, this project “examines America’s response to one of the greatest humanitarian crises of the twentieth century. Americans consider themselves a “nation of immigrants,” but as the catastrophe of the Holocaust unfolded in Europe, the United States proved unwilling to open its doors to more than a fraction of the hundreds of thousands of desperate people seeking refuge. Through riveting firsthand testimony of witnesses and survivors who as children endured persecution, violence, and flight as their families tried to escape Hitler, this series delves deeply into the tragic human consequences of public indifference, bureaucratic red tape, and restrictive quota laws in America.” Antisemitism in the US existed since colonial times and continued in various forms. Fundamentally, as the country evolved and became more diverse culturally and religiously, responses to this pluralism provoked isolationism and entrenched racism. The “Great Replacement” theme was stressed by highlighting the supposed threat of Jews and other immigrants replacing Native Americans. Antisemitic activists in the 1920s and 1930s were led by Henry Ford and other figures like William Dudley Pelley, Charles Coughlin, and Gerald L. K. Smith, as well as the Ku Klux Klan. They promulgated various interrelated conspiracy theories that widely spread the fear that Jews were working for the destruction or replacement of white Americans and Christianity in the U.S. The roots of the “Great Replacement” endures today in white nationalism, populism, and nativism. Although we moved from our image of a country as Anglo-Saxon to Judeo-Christian (Today how do we include all of the others outside Judaism and Christianity?), there is much to do yet. On October 27, 2018, the very first time we gathered as an interfaith community in this same synagogue, another mass shooting took place at the Tree of Life, or L ‘Simcha Congregation Synagogue in the Squirrel Hill neighborhood of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Protesting a Jewish immigrant service that provides humanitarian relief to refugees, Bower said on social media, “They like to bring invaders in that kill our people. I can’t sit by and watch my people get slaughtered. Screw your optics, I’m going in.” Eleven people were killed, and six people were wounded. Jewish Communities and Their Allies Rabbi Mimi went on to say how her mindset that Jews were alone in the world was not quite as accurate as she thought. She discovered stories of non-Jews who put themselves at great risk to hide and rescue her people running from Nazi persecution. It was palpable for her, connecting her to her family in those very days. She underlined that the Jewish community today cannot engage with antisemitism alone and that allies were crucial, what I see as the power of #oneinterfaithvoice. She recounted in our town where Rev. Bonnie and I collaborated to have Nazi war memorabilia removed from a local antique shop. She emphasized in our little town and everywhere else, how our one interfaith voice is crucial to creating inclusive communities in a world with pronounced divisions of antisemitism, Islamophobia, xenophobia, and racism at their core. Our evening prayer of Yom Kippur raises up our common oaths to God, and thus to each other, in vivid expectation of what our communities could be like if only we “listen” to the God who speaks to all of humanity in extraordinary ways. According to tradition, it is on Yom Kippur that God decides each person’s fate, so Jews are encouraged to make amends and ask forgiveness for sins committed during the past year. In our Metrowest Interfaith Dialogue Project, we are learning how to listen, act and renew our covenant with God and with each other. In my own Christian faith, it is about seeing each other as God sees us, and imagining a world together that are like icons, views of the dreams of God. אמן

Amen

6 Comments

The Berkley Center’s 2008 Undergraduate Fellows Program provided a select group of ten Georgetown undergraduate students with the resources to study

interreligious marriages in America. Starting in January 2008, the Fellows elected project managers and defined specific roles and responsibilities within the team. They met bi-weekly throughout the year to discuss the developments and progress of their research and analysis. They interviewed forty-five different couples focusing on the challenges and benefits that arise within interreligious marriage on a personal level to provide qualitative insights to this growing area of research. he interviews were divided into four religious' combinations: Jewish–Christian, Muslim–Christian, Hindu–Christian, and Buddhist–Christian. With directing and editing assistance from Dean Chester Gillis, the director of the Program on the Church and Interreligious Dialogue; Erika B. Seamon, a Ph.D. student in Religious Pluralism; and Melody Fox Ahmed, Program Manager at the Berkley Center, the Fellows developed the following report. the Fellows hope to provide insight into the lives of people that practice religious tolerance daily and hope that these findings will not only provide further information about the challenges and benefits of interreligious marriage but will also offer a micro-level view of religious tolerance that can be a model of global dynamics. By Lyz Liddell, Director of Campus Organizing, Secular Student Alliance Lori Fazzino, a non-religious friend of mine and sociology professor, shared this article in a package for secular students going back to college this fall. It has all kinds of possibilities for us in interfaith dialogue, from the perspective of the nonreligious. “Interfaith” has become a major priority on many campuses. Organizations are springing up to promote it, colleges and universities are embracing it, even the White House is reaching out to get involved. But there’s still plenty of confusion out there as to what interfaith is, and even more confusion from the nontheistic perspective.

In October 2010, I attended an Interfaith Leadership Institute hosted by the Interfaith Youth Core (IFYC) as a “campus ally.” This opportunity to participate in a two-day interfaith program helped me to understand exactly what this movement is and how we, as people with secular worldviews, fit into it. Interfaith is a rising trend, particularly on college campuses. It brings together individuals of differing worldviews (not just religious or theistic) to set aside their differences in order to accomplish shared goals. In many ways, the interfaith movement is tapping into people’s religious traditions to get them involved in activities that look a lot like real, secular pluralism. There are a lot of misconceptions about what interfaith programs are and are not. In the experiences I’ve had, interfaith is often an effort toward pluralism, setting aside our differences and trying to understand one another. It’s an effort to bring people together for social action or service projects. We can also make a list of what interfaith is not. Interfaith is absolutely not an opportunity for anyone to proselytize one another - from one religion to another, religious to nonreligious, or nonreligious to religious. And while we may set aside our differences, interfaith isn’t trying to pretend that we don’t have differences. It is not an effort to give religion a special place in society or on campus, nor is it an effort to make everyone the same. As nonbelievers, getting involved in interfaith has some awesome features. It’s a great opportunity for large-scale service projects, and it can help make nontheists more visible. It’s a chance to demonstrate that we can be “good without God.” On campus, interfaith programs can mean opportunities for representation or access to special funding or facilities. Last but not least, participation in interfaith programs can build relationships that help facilitate times when conflict does arise. But as with anything, there are some downsides. It can be hard for a brazen nontheist to set aside the need to question and challenge religion. Because of the name “interfaith,” outsiders might think that atheism is just another religion. Some interfaith programs aren’t as welcoming to nontheists as others, and sometimes they may require limiting or uncomfortable “mutual respect” agreements. Sometimes these are challenges to overcome and opportunities to educate our communities about nontheism; other times, there may be reasons to decline participation in an interfaith program. Every nontheist and every group is different and will have to decide based on their own circumstances whether interfaith participation is right for them. Despite these drawbacks, I still encourage nontheists to participate in interfaith programs. Be prepared, though, because certain situations are very likely to come up. Language is the biggest area to be prepared for. Interfaith programs are still figuring out that “people of all religions” doesn’t cover everyone, and sometimes you’ll hear people using words like “spirituality.” Generally speaking, take it in the spirit it was meant most of the time, language like this is a result of people and programs working to establish new ways of discussing a variety of worldviews and identities, and it is not meant to exclude or insult anyone. Likewise, it’s very common to encounter misconceptions and stereotypes about nonbelievers. Sometimes a group may face outright discrimination from an interfaith program. These situations can be handled through preparation and patience - and admittedly these problems aren’t limited to the realm of interfaith. With theists and nontheists both working to reach out to one another, we can’t help but make a difference in the world. And that’s something to get excited about! To read the full article, visit: foundationbeyondbelief.org/resources/pdfs/Atheists_in_Interfaith.pdf By Silma Suba | AUG 5, 2022 | Interfaith America Ten years ago today, on August 5, 2012, 17-year-old Harmeet Kaur Kamboj had just graduated high school and was in a bus full of family and relatives driving to Michigan from Virginia for their cousin’s wedding. There was an air of merriment all around the bus, people dancing, singing, and laughing, while some took a nap in anticipation of the long festive weekend that lay ahead. Kamboj remembers an aunt who was scrolling on her phone and broke the news to the wedding party: there had been a mass shooting at a gurdwara – the Sikh Temple of Wisconsin – where a white supremacist had open fired and killed six people. A seventh victim suffered serious injuries and would die from their wounds in 2020.

“It was hard to process at that moment. We were headed to this festive fun-filled event to celebrate new relationships that were being built, and at the same time we were having to hold all that pain too,” Kamboj says. “I was experiencing a whole new opposing set of emotions, and it took me a few days individually to process exactly what had happened.” In the days following the shooting, Kamboj recalls the frustration they felt watching the news coverage of the shooting and felt not enough was being done to offer support to the Sikh community. Today, Kamboj is an interfaith leader who works as a program manager for Interfaith America, and they are committed to centering the voice of Sikh Americans in their work. In commemoration of the 10-year-anniversary of the Oak Creek shooting, Kamboj has been supporting the Sikh Temple of Wisconsin, Sikh Coalition, The Interfaith Conference of Greater Milwaukee, and Sikh American Legal Defense and Educational Fund to host a series of workshops, a vigil, and panel discussions. They will also be leading an interfaith bridgebuilding workshop on Saturday, August 6, at The Sikh Temple of Wisconsin. In conversation with Silma Suba, media manager and staff writer at Interfaith America Magazine, Kamboj reflects on how the Oak Creek shooting impacted their work, and the 10-year-anniversary events. The conversation has been edited for clarity and length. How did the Oak Creek shooting impact the work that you have done in the past decade? Kamboj: It was a very formative experience, because I remember vividly the news coverage in the days and weeks following the shooting. I was really frustrated by it and upset by that coverage, because so much of it was not to memorialize the victims of the shooting, to understand the reason behind this tragedy, but rather, every new segment or article was kind of like a “Who are Sikhs? 101 Primer,” because a lot of Americans don’t know my community. They don’t know who we are and what we stand for. I was frustrated on a couple of levels. We were trying to mourn this loss of life and loss of community and loss of safety, and the only thing that the public is asking us is “who are you?” rather than asking “what can we do to support you? How can we make you feel like real members of this society, like true members of society?” When I started in interfaith work, I knew that my commitment personally had to be to fronting my community’s needs and centering those who are most marginalized, who are pushed most to the fringes of the Interfaith movement and of religious spaces in the United States, because we deserved way more than that at that moment. We deserved more support, more empathy, and more resources, and we were asked at that moment, just to give more labor to education and awareness. And so that very much informed me of the work that I began doing in interfaith spaces. Can you tell us about the interfaith workshop you’ll be leading at the 10-year-anniversary event at The Sikh Temple of Wisconsin? A huge contingent of interfaith leaders are expected to be in attendance because the weekend’s events are co-sponsored by the Interfaith Conference of Greater Milwaukee. Thinking about Interfaith America’s work, especially our new work around bridgebuilding, I knew that it was going to be a significant and important way for us to contribute to the event. Because there was so much more that interfaith leaders and Interfaith organizers could have done in the immediate aftermath of Oak Creek, that wasn’t done because of so many reasons, lack of awareness, lack of resources, lack of knowledge or understanding about who this community is and what we need in these kinds of moments. When I think about interfaith bridge building, which is the workshop I will be leading, it is about creating reciprocal and mutual relationships across lines of difference. At the end of the day, it’s about understanding that the landscape of religious diversity in the United States is not always totally understood. I think the religious landscape in the United States is underscored often, because communities like mine are, in comparison, much smaller than communities of the Abrahamic faiths and others. So, when we talk about the importance of interfaith bridge building, part of that conversation has to be about how do we support religious minority communities, not only in the face of tragedy but overall? So, the part of that workshop is not only around how to build relationships with the perceived other, but how do we acknowledge the privilege and power that some communities have in relation to others. How do you use that privilege to empower, to really invest in and support communities that do not have access to that kind of privilege and power. What will interfaith work look like during the 10-year-anniversary commemoration of the Oak Creek shooting? During the Thursday series of panels at Oak Creek City Hall, there’s at least one interfaith panel on public safety and safety for religious communities that I think is really important, because, particularly in the last five years, mass shootings and houses of worship have become a frequent headline. This is a way for interfaith leaders and communities dedicated to interfaith to come together and not only support each other but think together about ways to ensure our safety mutually. The candlelight vigil on Friday (August 5) is going to be a powerful way for folks of many traditions to come together and share practices and theologies of mourning and grief and recovery in light of this event. And Saturday, a series of events at the gurdwara is a really intimate way for folks who are dedicated to interfaith work to really come out in support of this community. I think that oftentimes we overcomplicate how we can show up in interfaith spaces, and oftentimes, it just means showing up and participating and being physically, emotionally, mentally present. And that’s really what the Saturday series of events is all about. These are community events, workshops, tours of the gurdwara, and talks about Sikhism and the Sikh community rooted in Oak Creek. And it really is open to anyone and everyone because that sort of showing up is so important at this time. The Metrowest Interfaith Dialogue Project, a special project of Our Lady of Fatima Shrine, Holliston, sponsored an evening of sharing across faiths. On Tuesday, December 7, multifaith neighbors gathered around a fascinating conversation and surprising connections with Hindus, Christians, and Sikhs. Swami Tyagananda, head of the Vedanta Society of Boston, presented some central tenants from his recent publication, Looking Deeply on Hindu discernment and our relationships with each other, the earth, and the Divine, or God. In response to Swami’s presentation, Siri Karm Singh Khalsa, of the Sikh community of Millis, and Fr. Carl Chudy presented responses to the presentation through the lens of Sikhism and Christianity. Here is the Christian response from Fr. Chudy.

A Christian Response to Swami Tyagananda’ s Looking Deeply I want to thank Swami Tyagananda for accepting to share his work with our interfaith community and frankly found it a fantastic opportunity to deepen my interfaith literacy around the Advaita Vedanta tradition of Hinduism. This ancient text teaches something at the heart of Christianity in many different forms, and that is the art of discernment or the discrimination between what I understand in Hinduism, the real (unchanging, eternal) and the unreal (changing, temporal). The description in the introduction of how this understanding begins is all about “looking at everything with care and attention.” (8). As Swami Tyagananda points out, this is not just an intellectual exercise but something at the heart of our experiences that we can become aware of in profound ways. He says: “Everything that we see with the senses and imagination with the mind is the result of misperception. When we look deeply, we clearly see the truth of nonduality.” (9) Nonduality is a notion in Christian spirituality and prayer that is just recovering from centuries-old traditions that go back to ancient contemplative prayer traditions and cosmologies. Fr. Richard Rohr, Franciscan spiritual master, and therapist are one of those voices today reasserting nonduality for Christians. He says: “Contemplation teaches a different mind which leaves itself open so that when the “biggies” come along (love, suffering, death, infinity, contradictions, God, and probably sexuality), we remain with an open field. We don’t just close down when it doesn’t make full sense, or we are not in full control, or we immediately feel validated. That calm and non-egocentric mind is called contemplative, or non-dual thinking.” In this sense, Christian nonduality is the ability to hold the tension of opposites, rest comfortably in ambiguity, and resist the temptation to demonization and exclusion. For me, this comes up, particularly in my interfaith dialogue work. Through its many expressions, Christianity has historically tended toward exclusivism, that we are the only real authentic expression of God’s mercy through Jesus Christ, and all other faiths are too, but to a lesser degree. This exclusiveness reveals a tendency between spiritual arrogance and an open mind to our religious differences that we cannot easily explain. Holding this tension is crucial to any authentic interfaith dialogue that respects all parties and understands God’s mysteries that are beyond us and our religious traditions. Nondual thinking allows us to remain in that creative tension and explore not only our commonalities but also what our differences may teach us. This sense of nondualism also arises in our contemplative prayer traditions for what Christian tradition has classically known as “the unitive state,” the highest level of spiritual attainment according to the traditional tripartite road map of “purgative,” “illuminative,” and “unitive.” [[1] Both nondual or the “real me” Both traditions hint at a permanent, irreversible shift in the seat of selfhood and in the perceptual field that flows out from this new identity. The former, nucleated sense of selfhood dissolves, and in its place, there arises a capacity to live a flowing, unbounded life in which the person becomes “one” with God (as the Christian mystic Julian of Norwich famously expressed it) and one with one’s neighbor, flowing in the fundamental matrix of love without the need for either edges or centers.[2] Finally, the Hindu sense of consciousness reflects the nondual or true self, which is birthless and deathless, pure, and perfect, as Swami Tyagananda shares. For Christians, Jesus Christ was born as the human face of God. Taking the God-made human image seriously, we understand this inner divine image imprinted within humanity as our true self. It is our best self, our kindest, more inclusive self. This is amplified in the boundary-breaking of Jesus reflected in the Christian scriptures who reached beyond his own race and religion and sought out all through stories of the Good Samaritan, pointing to the extraordinary faith of those whom his contemporary faith leaders cast as faithless and far from God: the prostitute, the leprous, the foreigner, etc. The early Christian communities reached out to all of the Mediterranean and Asia up to China in its first five hundred years beyond its Palestinian Jewish roots. In that growing, historical journey toward the mystery of Christ in all things in mysterious ways, we are still living discerning today. Fr. Carl Chudy, SX [1] One explanation of the Three Ways states that at the Purgative stage, the beginner is standing in cold water in the wading section of the pool. In the Illuminative stage, the person is in the deep end of the pool and is treading water but has learned how to trust that God will supply the grace needed. In the Unitive stage, the person is in the middle of the ocean during a total tempest. This stage requires total surrender in the face of the infinity and obscurity of a loving God. The prayer at this level is the most faithful, most trusting, and most loving with a love which is agape—a total self-oblation to God in love. (Stages-of-Spiritual-Journey-by-St-John-of-Cross.pdf (christinasemmens.com) [2] Bourgeault, Cynthia. The Heart of Centering Prayer (p. 46). Shambhala. Kindle Edition. Most of us have faced situations in life when we are confused and unsure about how to proceed. We have wondered: “What is my duty in these circumstances?” Often we just muddle through the confusion and use whatever justifications the mind can think up to determine the best course of action. What if we yearned for scriptural guidance in this matter? Do our ancient books have any useful insights that may help us figure out what our duty is?

Arjuna had a duty-related dilemma on the battlefield of Kurukshetra, as we read in the Gītā. Thrust into a war with people who Arjuna saw as his own, he was confused about the right course of action. He sought Krishna’s counsel. Krishna’s advice to Arjuna was simple: Do your duty. Krishna went so far as to say that it was better to die doing one’s own duty, even if imperfectly, than to attempt to do someone else’s duty, however perfectly (3.35, 18.47). The word that Krishna used repeatedly for “one’s own duty” was svadharma, literally, “my dharma” (2.31, 2.33, 3.35, 18.47). Derived from the root dhṛ, “to hold” or “to support,” dharma covers a large canvas, so it is difficult to find a one-word translation of it in English. Depending on the context, dharma can be translated as duty, virtue, justice, and even religion. In order to understand svadharma, we must first learn a little about dharma as duty. A good starting point in the examination of dharma is to know that it can be divided broadly into two categories: generic (sādhāraṇa) and specific (viśeṣa). As the name suggests, generic dharma is meant for all. It includes virtues like non-injury (ahiṁsā), forbearance (kṣamā), sense-control (indriya-nigraha), compassion (dayā), charity (dāna), purity (śauca), truthfulness (satya), austerity (tapas). Everyone is expected to develop these qualities. The generic dharma is universal. It is dharma for all. It is dharma as virtue. Dharma as Duty Everyone has a specific dharma as well. This is dharma as duty. This usually includes duties associated with one’s stage of life (āśrama) and one’s position (varṇa) in the community. In the early stages of Indian society, there were said to be four stages in life: the student stage (brahmacarya), the married stage (gārhasthya), the retired stage (vānaprasthya), and the hermit stage (sannyāsa). In our times, these have largely been reduced to three: the first part of life is the student stage, usually under the care of one’s parents. Then comes the married stage, when one launches into a career and starts one’s family. Finally, the retired stage, when it’s time to retire as the children grow up and start their own families. A few among those in the retired stage may eventually become hermits without taking formal monastic vows. Those who do take formal vows usually begin early in life, often during or immediately after the student stage. Every one of these stages has its own special set of duties called āśrama dharma. In the student stage, for instance, the primary duty is to study. But students are at the same time also sons or daughters, so they have duties toward their parents as well. In the married stage, more duties are added—such as the duty towards the spouse and the children—and some of the old duties continue, the duty toward one’s aging parents, for instance. In this way, every new stage adds more duties while retaining a few from the earlier stages. The only exception to this is the last stage. Those who are in the hermit stage are exempt from all the earlier duties, but they have a special set of duties associated with the monastic life. As to one’s duty toward the community (varṇa dharma), four fields in community life became the focus of attention early on: religion, administration, commerce, and service. Every community needed scholars and priests (brāhmaṇa), administrators and warriors (kṣatriya), farmers and traders (vaiśya), and help of nonspecialist workers (śūdra). Every one of these positions had a set of duties assigned to it. The nuts and bolts of this system evolved over a period of time, the natural way social structures have always taken shape. The Past How were the positions determined for community members? On the basis of the qualities (guṇa) they possessed to do the work (karma) that was required (Gītā 4.13). While this was a logical way to fulfill the needs of a community, it couldn’t have been easy centuries ago to implement it in practice. In many ways the world then was unimaginably different from the world today. For starters, these ancient communities were mostly isolated from one another and therefore had to be self-sufficient. Travel was rare and, in the absence of any meaningful mode of transport, didn’t take people far from their homes. Almost everyone grew up, worked, married, raised children, retired, and died in the area where they were born. There were no schools to go to for professional training. The only way healing could be learnt, for instance, was as an apprentice to a physician (vaidya). The village physician’s assistant would usually be his own son, who would grow up and, when his father retired, take his place. There was no guarantee that the physician’s son was the best candidate for the job or even had interest in it. But he didn’t have much freedom to choose some other career. If there was only one physician in the village and he died, the community couldn’t go without a physician just because the apprentice wasn’t interested in the job. Similar was the situation for other skills and trades needed for an efficient functioning of the community. There were exceptions in extraordinary circumstances, but they were rare. It clearly wasn’t an ideal situation, but there didn’t seem to be any better alternative. The idea was good but the infrastructure was not congenial. That is how these work-related obligations came to be inherited and stayed within the family, not so much earned through merit. Over the years, the positions hardened and came to be determined by birth (jāti) and identified by the work the people did. Swami Vivekananda referred to the arrangement as “a hereditary trade guild” (CW, 5. 311) and “a social institution” (CW, 1. 22). Fully aware of how it was being portrayed, Swamiji emphasized that it was a mistake to view it as “a religious institution” (CW, 2. 515, 5. 22). The varṇas are mentioned by name in the Puruṣa-sūkta of the Ṛgveda (10.90) and in the Gītā (4.13, 18.41-44), but that doesn’t make the social system that adopted the varṇa nomenclature a religious institution, any more than the many references to slaves and slavery in the Bible make that a religious institution. What the groupings in the Indian society led to was a situation that pitted heredity against merit. People claimed a position because of heredity, which determined the work they did. In many instances, there were perhaps others who were better suited to the position because they had the qualities essential for it. But such people did not always get the job even when they yearned for it. Heredity and work were easier to identify objectively than interest and aptitude. The result was that one’s family affiliation and the inherited work became the socially accepted markers of one’s position and responsibility. To be sure, qualities were not ignored. They were often recognized and utilized, but they could not dislodge the primacy of heredity. In the Mahabharata, for instance, Vidura was by birth a śūdra and maintained that position socially but, because he had qualities identified with the position of brāhmaṇa, functioned as a much-respected advisor to the king. On the other hand, Droṇa, who was a brāhmaṇa by birth, was skilled in archery and taught military arts, work that was associated with the kṣatriya position. These were not exceptions. It was not unusual to have one position claimed by birth and another earned through merit or imposed by circumstances. This has continued to be the case, though hereditary positions are increasingly becoming irrelevant now. The original system was designed for a fair distribution of responsibility among community members. Every form of work that met the social need was necessary and important. There wasn’t any inbuilt sense of one work being higher or superior to any other work. There was no sense of hierarchy. The work was not meant to be an end in itself. It was a means. It could bestow bliss in heaven after death or, when done as yoga, it could lead to spiritual liberation (mokṣa). Every form of work, so long as it did not violate moral and ethical principles, had the ability to give us the highest (Gītā 18.45-46). It didn’t therefore matter what work people did, so long as they remained true to dharma as virtue. In practice, though, things didn’t work out quite so ideally. We don’t know how long it was before hierarchies arose with everyone claiming themselves to be superior to others and hence more important than others. The problem was what it has always been throughout human history—greed and selfishness. What had begun primarily as an equitable distribution of duties for social upkeep changed over time into a politicized preservation of privilege for the powerful. The history of the world repeatedly shows us that we human beings are adept in the art of transforming anything good into something awful. Every form of responsibility brings power and, along with it, the desperate desire to preserve privilege. The priests had knowledge gathered from ancient books and they used fear of retribution in the afterlife to keep the rest under their thumb. The warriors brandished the power of weapons and no one dared to refuse whatever they asked for. The traders used their commercial might to control and subdue others. The workers bore the greatest brunt, being oppressed in one way or another by the priests, the warriors and the traders. Eventually they too found their voice and discovered their own strength in numbers and used it to good effect through strikes and protests. Not all of these things happened at the same time and to the same degree. Also, not everyone misused their positions. Some were indeed good and responsible people, but many others were not. At different times and in different communities, one or the other of these four power centers dominated and tried to control the rest. The emphasis shifted from duty (dharma) to rights (adhikāra). Duty required us to give our time, energy and skills. Rights were about receiving more power, more privilege. No wonder duties were ignored and there was a rush for rights, a trend that continues to this day, not only in the Indian society but also in the rest of the world. The Present The constitutions of democratic nations the world over list different kinds of rights that citizens have. It will be difficult to find any mention of duties. How can there be any rights without the corresponding duties? When President Kennedy said at his inauguration in 1961: “Ask not what your country can do for you, ask what you can do for your country,” he was hoping that his fellow Americans would redirect their attention to duties, not simply remain fixated on rights. The world today is radically different from what it was in those ancient days centuries ago when the social order in India was evolving. The constraints of those early communities no longer exist. No longer is one community isolated from another to the extent it was in the past. On the contrary, we are more connected than ever—in person through easy jet travel and virtually via the internet. Global trade and commerce have not only brought people together but also made it possible to shop for talents and skills in every part of the world. Oddly enough, the original intent of the varṇa-system to have responsibilities divided in a community on the basis of merit is easier to implement now than it was then. If a certain skillset is missing, we can now import it from elsewhere—or outsource the work some place else when possible. Today’s businesses try to employ the best talents suited for the job, for that’s the key to success and profits. Merit has a better chance today than it had in the past. Because a lot more choices are available, it is easier now to choose our careers and pursue our interests. There is more freedom in social matters than ever before. It would seem that things are finally falling in place. If you feel that this scenario looks too rosy to be true, you are right. It does represent truth, but only a half-truth. The other half isn’t pretty. We have come far from the isolated but mostly homogeneous communities of the past to the closely connected but increasingly diverse world of the present. Inevitably, hurdles have cropped up. Merit is still recognized, but before it can assert itself, it has to battle the compulsions of poverty and the forces of racism, antisemitism, nationalism, and fundamentalism. These have spawned different kinds of power centers in societies the world over, keeping communities internally divided. The claims of merit take a backseat when a person is not of the right color or the right nationality or the right religion. More important than the needs of the community are the preservation of privilege of the group in power. The “group in power” is the dominant caste of the time. When India came under the thousand-year rule of people from beyond its borders, its social structure had already undergone a sea change. The society was no longer being nourished by dharma as duty. Dharma did not disappear but it became weak. The masses were being controlled by those who had usurped power and privilege. Swami Vivekananda was unsparing in his condemnation of those who exploited the situation to their own advantage. The shell of the original system survived but its soul had vanished. This did more harm than good to the health of the community—and was one of the major reasons why India could not defend itself from external aggressions. Arriving in India in 1498, the Portuguese were the first to apply the word “caste” (from Portuguese, casta) to the hereditary groupings in Indian society. Throughout history, the powerful—in India’s case, the colonial masters—have always had the privilege of defining and stereotyping the less powerful. Thanks to the Portuguese and then the British, the word “caste” got indelibly associated with India. Because the varṇa system by then had become a caricature of its original plan, “caste” remained as a taint on the Indian society and, oddly, also on Hinduism, the religion that majority of Indians practice. It is difficult to find today a textbook or a chapter on Hinduism that doesn’t treat caste as if it were the defining part of the tradition. Isabel Wilkerson points out in her insightful study, Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents (2020), that the problems in today’s America—especially the ones faced by the black community—are better understood through the lens of caste than racism. A system of artificially constructed hierarchies exists not only in America but throughout the world and, even though it may not always be called by its true name “caste,” it continues to be the major cause of social discontent and suffering. The system takes different forms and manifests in different ways, discriminating against people on the basis of ancestry, color, class, faith, nature of work, and sexual orientation. The word “caste” may have been employed extensively with regard to the Indian society, but it is not merely an Indian problem. It is a global problem. We have seen that the era in which the varṇa system emerged in India has long passed. The social arrangement, whatever good it may have achieved in the early days, fizzled out with the passage of time due to selfishness and greed. There was no conscious and collective effort to modify or revise the social structure periodically to keep in step with the rapidly evolving society. All social institutions that stagnate tend toward chaos and corruption. Reformers in every generation tried to stem the slide, but their efforts were clearly not enough. All of this has made the system untenable today and irrelevant to most Indians, especially those living in urban areas. How does it still manage to survive? It has not survived in its original form obviously. What survives now is the empty shell that bestows privilege on the powerful and keeps the less powerful suppressed through political maneuverings. The underprivileged are nevertheless lulled into clinging to their group identities by the crumbs of “benefits” doled out to them by their political patrons. Each of these “castes” has become a special interest group and is kept alive by community leaders as “vote banks” to strengthen their political clout. The phenomenon is not limited to Indian politics. The caste structure in different guises exists all over the world and shows similar manipulations by the people in power. So, what is “my duty”? Keeping all of the above in mind, it’s time to ask: Does the Gītā teaching regarding dharma as duty have any relevance in the 21st century? How can I be sure that I am truly following “my dharma” (svadharma)? What is my dharma in today’s changed world? As we have seen, “my dharma” includes two sets of primary responsibilities: one, depending on the stage of my life (student, family, retirement, monastic), and two, depending on my skills and work for the community. A group of ancient books called Dharma Śāstras deals with duties at different stages of life (āśrama dharma). These books haven’t been updated for centuries, so their practical utility is limited. They are generally of interest to theologians or to those who study history of religion. For the rest of us, no books are really needed. Common sense would be more than enough, if it is accompanied by a firm determination to follow dharma as virtue. What is my varṇa dharma? Let us return to the Gītā idea (4.13) of varṇa dharma being determined by the qualities (guṇa) required to do every work (karma). In Arjuna’s case, he was a kṣatriya because he had the requisite qualities, not merely because he was born in a kṣatriya family. He was the preeminent archer of his time. Krishna reminded Arjuna that his varṇa dharma required of him to vanquish the oppressors and uphold justice (2.31, 11.33). Overwhelmed by his filial attachment to members of his family who were on the opposite side, Arjuna wanted to give everything up and live on alms (2.5), a monastic lifestyle for which he wasn’t qualified yet. His knowledge of who he was and where his duty lay got clouded by his confusion. That is precisely the kind of confusion that can come upon me if I lack self-knowledge—“self” with the lowercase “s”—meaning, plain simple knowledge of who I am at this moment. In order to know myself, I should look within to examine what my inherent talents and qualities are. It is not easy to look at oneself objectively and assess one’s worth. Some amount of ego reduction is necessary in order to be able to do that well. Done clumsily, people either underestimate themselves or grossly exaggerate their worth. Armed with the knowledge of my strengths and my weaknesses, my skills and my interests, I can choose my career and decide what else I should do in life. If my self-assessment is accurate, my varṇa dharma becomes obvious. If I am lucky, I’ll find the kind of work I love and am good at. All I need to do then is to work hard, be sincere and attentive. That will bring me joy and other rewards. I can also help those around me find work and activities that fit their profile and interests. The secret of happiness is to make others happy, especially those in my immediate circle. I cannot be happy if everyone around me is unhappy. It’s also possible that, for whatever reason, I may not find the work that I love or the work I am qualified for. I may then have to settle for something less interesting. The work I am saddled with may not feel to be my svadharma at all. I may feel that my merit is not being recognized. When that happens, it is easy to feel frustrated and angry. But it doesn’t really help. When such impulses go unchecked, they can lead me into doing things that produce even more suffering. I need to find other ways to deal with my situation. One practical way is to do what work I can for the present while looking out for opportunities to do what truly matches my skills and aspirations. Patience and perseverance have never hurt anyone and usually are rewarded sooner or later. Who wouldn’t want a work that is enjoyable and fulfilling? What if I am not so lucky to get it even after trying my best? If I am a devotee or a spiritual seeker, I will then view whatever work becomes mine as something that God wants me to do. I’ll remind myself that God has put me in this situation for a reason. It’s necessary for me to learn some lessons in life that I haven’t learnt yet. No matter how boring or uninspiring, I’ll try to do the work to the best of my ability, as skillfully as I can, in a spirit of karma yoga, recognizing that doing the work in this manner is my svadharma now. All of this applies not only to the work I do to earn my livelihood but also to every other activity of mine. The truth is that when we do something in the spirit of karma yoga, it somehow becomes meaningful and joyful even if it wasn’t something we were originally thrilled about. Not many realize that all work is really done by God. This is not recognized because the ego gets in the way and appropriates all agency to itself. If we succeed in minimizing—and then eliminating—the ego, we will know that all efforts are powered by God, who pervades everything and everyone. Every duty stops being “duty” when done as karma yoga, it becomes a form of worship, and leads to perfection and spiritual freedom (Gītā 18.46). We don’t know if there will ever be a time when everyone in the world will realize this. It sure feels unlikely. Be that as it may, no power in the world can stop me from thinking that every work that makes me unselfish is my duty. Every work that is powered through love and kindness is my duty. Every work that is based on truth is my duty. Every work done in a spirit of worship is my duty. Not only should I think this way, I should also live this way day after day, month after month, year after year. If I do this, nothing else matters. If I don’t do this, what does my life matter? The Islamic Society of Framingham

The Islamic Center of Boston, Wayland Islamic Masumeem Center of New England, Hopkinton To our dear neighbors in faith, To our utter horror we woke to the news, as you had, to the horrific killing and wounding of worshipers in houses of God in Christchurch in New Zealand. The hate that mustered these killings is sadly experienced in many places in the world today, including our own nation, the United States. They express themselves through the wounds of Islamophobia, antisemitism, overt racism, and xenophobia. In recent months our own communities have not been immune to some form of this social hatred toward our neighbors and friends. As clergy of Holliston, we stand with you and for you in this most grevious time. We offer our prayer to God as he holds our grief and fear in these challenging times. We also offer our hands and our hearts with the hope that together we can heal these wounds of hate in our own communities, and together with others, throughout our nation and world. We want to reach out to you in this difficult time and together say that we utterly condemn these murderous actions and pledge to work in bringing all of our religious and nonreligious communities together in dialogue and cooperation. The use of social media as a tool of terrorism cannot be overlooked. The heinous nature of the original attack is only compounded by the use of social media to spread further fear and terror in its wake. The use of social media, and the connection to online hate speech groups, is a clear reminder to us that violent extremists of all stripes are using social media to spread hate speech, and incitement to violence. We must do more in our communities to combat online hate and religious bias. We extend our heartfelt condolences to the families and friends of those killed and wounded in New Zealand, as we do so with you and your communities in the Metrowest area, and throughout the country. "Give glad tidings to those who patiently endure, who say when afflicted with a calamity: "To Allah we belong and to Him we return." They are those on whom (descend) blessings and mercy from their Lord, and they are the ones who receive guidance." (Surah Baqarah; 2:155-157) Rev. Bonnie Steinroeder Rev. Mark Peterson Rabbi Steve Edleman-Blank Fr. Carl Chudy Rev. Sarah Robbins-Cole Rabbi Jennifer Rudin Mr. Hussam Syed Mr. Larry Maloney METROWEST INTERFAITH DIALOGUE PROJECT By Larry Maloney

Everyone says forgiveness is a lovely idea, until they have something to forgive,” wrote CS Lewis, one of the last century’s most noted Christian writers. Yet few people will ever encounter the daunting forgiveness challenge that Simon Wiesenthal, the famous Nazi hunter, faced during his imprisonment in a Nazi concentration camp. Witnessing the deaths of his fellow Jewish prisoners on an almost daily basis, the young Wiesenthal one day finds himself face to face with a dying SS soldier who asks Simon’s forgiveness for the Nazi trooper’s role in the slaughter of 300 Jews in a Russian town. Wiesenthal recalls that incident and his personal struggle with the question of forgiveness in The Sunflower, a book that has become central to Holocaust studies since it was first published in 1976. The book asks readers what they would have done in Simon’s place and includes perspectives from 40 commentators, including well-known theologians, writers, professors, as well as Holocaust survivors. On February 24, more than 30 Metrowest residents added their own views on The Sunflower’s key questions in a community book discussion and dinner hosted by Holliston’s First Congregational Church. The gathering was sponsored by the Metrowest Interfaith Dialogue Project (MIDP), launched in 2017 by Holliston clergy and the Islamic Society of Framingham to promote understanding and cooperation among people of diverse faiths. The group also reaches out to non-believers and to those who are not affiliated with any religious congregation. After a potluck supper, participants broke up into four groups to discuss the book, as well as their own opinions on forgiveness. Leading the discussions were four Holliston clergy: Rev. Bonnie Steinroeder, senior minister at the First Congregational Church, Rabbi Steven Edelman-Blank of Temple Beth Torah, Rev. Carl Chudy of Our Lady of Fatima Shrine, and the Rev. Mark Peterson, pastor of Christ the King Lutheran Church. Helping to lead Muslim participants in the discussion was Hussam Syed from the Islamic Society of Framingham. As the groups tackled the many issues raised by the book, some common questions surfaced: • Is one justified in forgiving someone on behalf of victims who cannot speak for themselves? • Can we forgive without also forgetting? • What are the necessary requirements of true repentance? • How culpable are those who remain silent in the face of wrongdoing? • For believers, what role does God play in human-to-human forgiveness? • How do different religious faiths –Judaism, Islam, Christianity, Hinduism, Buddhism – view forgiveness. Commentators from all these faiths give their perspectives in The Sunflower. Not surprisingly, many of the issues raised by this thought-provoking book remain unresolved in the minds of many readers. Yet participants in the Metrowest event seemed to agree with several of the book’s commentators on one important conclusion: the act of forgiving, no matter how difficult and painful, can remove great burdens not only from the wrong-doer but also from the one who has been hurt. (Larry Maloney is a freelance writer in Ashland, MA) Metrowest Interfaith Dialogue Project

hollistoninterfaith.org | [email protected] | Holliston, MA November 17, 2018 Dear Friends, Not long ago the news of a fifth-grade child in Hemenway school in Framingham, who was the victim of a hate crime based on her faith and the faith of her family devastated us all. This is an issue that is not new in our country, unfortunately, and one that we of different faith and non-faith traditions need always to be vigilant for. We pray for this child and her family and all our Muslim neighbors, near and far, who may struggle for acceptance in these fractious times. In many ways this act also symbolizes all of the acts of bias and violence against all those who are Muslim, Jewish, African American, immigrant and others in these recent years particularly. Last October 27th, we held our first interfaith event at Temple Beth Torah on the very afternoon of the anti-Semitic shooting at Tree of Life Synagogue in Pittsburgh. Unexpectedly we moved to Jewish prayers of mourning, and even though the circumstances were quite difficult, the opportunity for our non-Jewish neighbors to support our Jewish friends at such a time was indeed was what neighbors of faith must do. The attack on this child was not born in a vacuum, but part of a culture of prejudice where hate is learned, even by children. Our commitment to interfaith dialogue is to join others in support to this child and her family, but also to encourage opportunities where peoples of different faith traditions can come together in friendship, seeking common ground and holding our differences together in respect and curiosity. This is not only a demand of the best of each of our faiths, but this is also the stuff of nation building, starting in our communities. Shalom | Peace | Salam Rev. Bonnie Steinroeder – First Congregational Church, Holliston | Fr. Carl Chudy – Our Lady of Fatima Shrine, Holliston | Rabbi Steve Edelman-Blank – Temple Beth Torah | Rev. Mark Peterson – Christ the King Lutheran Church, Holliston | Rabbi Jennifer Rudin – Simcha Services, Holliston | Shaheen Aktar – Islamic Society of Boston | Hussam Syed – Islamic Society of Framingham |

AuthorFr. Carl Chudy Archives

June 2024

Categories |

||||||

RSS Feed

RSS Feed