|

Archbishop Gustavo Garcia-Siller, Bishop of the Diocese of San Antonio, Texas, profoundly stated in light of upcoming presidential elections: “Christians are not a social club that gathers on Sundays to receive nice-sounding catchphrases. We are to be a constant influence in society. Our identity as children of God involves a lifelong journey of struggle and testing. We are called to repent and continually transform our lives, thoughts, attitudes, and actions to live in a kingdom of justice, peace, mercy, fidelity, harmony, and unity.” (America: The Jesuit Review, 03/05/24) Considering our shared responsibility and influence as Christians in society, I firmly believe that the transformative power of the interfaith movement is a vital part of societal transformation in the United States. It's not just about dialogue between religious believers; it's about infusing new energy into democratic ideals that respect our diversity through the evolving interfaith and religious-secular solidarity for the common good. We, as a collective of believers and nonbelievers, are the ones who shape our communities and nation. When we view the interfaith movement in the U.S. as more than a commitment between different religious communities, we recognize its potential as a potent catalyst for reshaping our shared culture. By prioritizing the common good, we unlock the transformative power of religions. As Fr. Pawlikowski, a scholar in Jewish Christian relations, succinctly states, “Religions enable us to rise above situations where power fosters an environment of inequality.” Our National Discontent Amidst the spiritual, psychological, political, and social upheavals that have further polarized the United States, pluralistic solidarity's urgency and healing power have never been more crucial. The recent 2020 presidential elections, marred by contentious disputes over the electoral results, have inflicted deep wounds on our democracy. The threats against poll workers and the attempts by certain lawmakers to undermine the election results in Congress have eroded public trust in our electoral process, our democracy and the essential institutions that sustain it. This erosion of trust is a pressing issue, a call to immediate action for change. The tragic insurrection culminating from these events at the nation’s capital on January 6, 2021, gathered over 10,000 people in Washington, DC. Rioters smashed through barricades and ransacked the US Capitol, intending to stop the certification of President Joe Biden's election. As Trump supporters stalked the halls of Congress and lawmakers fled to safe rooms in fear, the country seemed united in its disgust. (ABCNews, Thursday, January 6, 2022) As we prepare for elections nationally and locally for 2024, where entire populations of Americans perceive the nation in starkly different ways, it is helpful to explore why religious institutions collectively are crucial to a vital democracy. Each religious community and its adherents express unique visions of the divine cosmos, the light of God reflected in everything, the spirituality and values expressed in our communities, and their unique shaping to a culture we all share. However, only one interfaith voice brings many voices together, which is a different and formidable power. Democracy Requires Interfaith Solidarity Jurgen Habermas, a secular philosopher, suggests that religion can remedy contemporary societal issues. It can inspire moral solidarity and political action, bridging social and economic divides. Members of a religious tradition share moral vocabularies (e.g., “Love your neighbor”) and narratives (e.g., parables) that impart concern for the vulnerable with profound meaning and inspire not just individuals but entire communities. On the other hand, a purely secular discourse devoid of religious influence offers a less robust foundation for collective action. It presents a more abstract view of the individual, emphasizing less the individual’s social relationships and responsibilities. In this sense, both the secular and the religious are complementary and essential in a dialogue between religious communities and secular civic institutions. (Dr. Michelle Dillon, Postsecular Catholicism, 2018) The purpose of these essential encounters always begins locally, with national and global implications. The words of Irish poet Padraig O Tuama truly resonate when he says we need to “find a way of navigating our differences that deepen our curiosity, deepen our friendships, deepen our capacity to disagree, deepen the argument of being alive.” It is not a given that pluralism leads to a more profound unity. An increase in diversity in the community ordinarily leads to a decrease in social trust. It is a work that needs to be positively and proactively engaged. (Robert Putnam, Diversity and Community in the 21st Century, 2007) As interfaith community members, how do we reconcile our profound differences while working towards a more peaceful and just world? We must not shy away from difficult questions. Two significant ways of seeing this in action are a national program, The Faith in Elections Playbook, and the other is a local program organized through the Xaverian Missionaries USA, The Metrowest Interfaith Community. A National and Local Experience Today, an essential interfaith organization in the country, Interfaith America, and a leading cross-partisan democracy nonprofit, Protect Democracy, launched the Faith in Elections Playbook. The Playbook, which will serve as an anchor for faith-based engagement throughout the 2024 primaries and into the general election, is a step-by-step guide for people of faith to bridge community divides, uplift trustworthy information; support voters with food, water, and a peaceful presence; recruit poll workers; build relationships with local election officials; and offer houses of worship as polling sites. The Faith in Elections Playbook project represents a unique partnership between one of the United States’ leading interfaith organizations and one of its most influential civic institutions, which sees faith as a foundational American strength. Its interfaith advisory council members represent a wide range of faith traditions, including Judaism, Islam, Sikhism, and multiple denominations of Christianity, including Catholicism and Evangelicalism. The work has already begun across a cluster of community groups, including faith communities, colleges and universities, and other sectors. A more local program involved in this tremendous national challenge is the Metrowest Interfaith Community, facilitated by the Xaverian Missionaries in Holliston, Massachusetts. It is a collaborative network of religious leaders, congregants, and others representing diverse faith traditions, including our friends and neighbors who don’t identify with any specific faith tradition. We attempt to unite members of our congregations, communities, and the larger public in the interfaith dialogue of life, religious experience, and the common good. In our community, Jews, Christians, Muslims, Sikhs, Hindus, Baha’i, and the “spiritual but not religious, began forming a multifaith and multi-spiritual community in 2018. Our first interfaith program occurred in the evening at our local synagogue, Temple Beth Torah. It was October 27th, and earlier that afternoon, there was an antisemitic terrorist attack that took place at the Tree of Life – Or L ‘Simcha Congregation synagogue in the Squirrel Hill neighborhood of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, United States. As we filed into the synagogue that evening, our plans for the joy of interfaith solidarity turned into Shiva, a period of mourning together. Grief is often too heavy for one person or even one community. That evening, we helped lift the grief of our Jewish neighbors together. Our work in addressing the great divides of antisemitism and Islamophobia, xenophobia, and racism became an integral part of our interfaith journey together. At the heart of much of the resentment and animosity of our political divides today, as we look to electing a new president and local officials, is an expression of these deeper divides in our human community. Collaborating with our civic institutions, the interfaith movement is a healing balm in a divided country. Ground Rules As we look to presidential elections this year, our politics, like interfaith collaboration, require specific ground rules. First, we should not expect perfection from ourselves, others, or even the place we come from. We should not claim innocence or speak only from our scars. We should recognize that truth and love can be increased when we connect with people correctly. Finally, our highest hope should be to grow together, creating a civic space to form a diverse community of hope. (From a People’s Supper, Faith Matters Network).

2 Comments

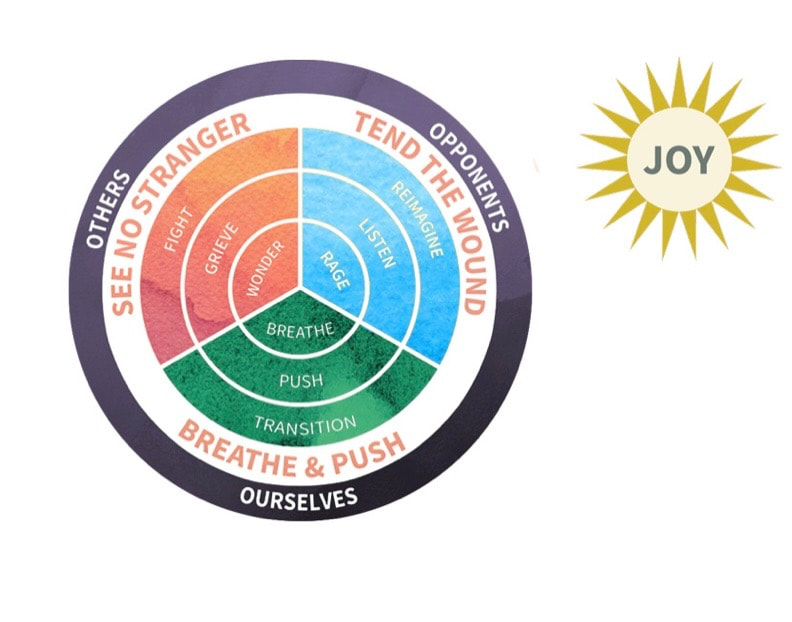

The Metrowest Interfaith Community offered a three-part opportunity to come together and study the work of Valarie Kaur, See No Stranger. It was an inspirational time that surprisingly allowed us to meet her at the end of the book discussion and to hear her speak of the times we live, not in the darkness of the tomb, but the darkness of the womb! One of the hardest things we can do as humans is to love our enemies past the harm and hurt they have caused. Valarie Kaur , author, and member of the Sikh faith has given us a book that can help us to do this work and a compass that lays out the steps in doing this. In See No Stranger: A Memoir and Manifesto of Revolutionary Love, Kaur provides us with a book that is part memoir and part how-to manual on how to practice what she describes as “revolutionary love”. She defines revolutionary love as the active decisions humans make to wonder about others, our opponents, and ourselves. This act of wonder, she says, will help make the world a better place. Failing to wonder ultimately leads to violence against people who we consider as the other. Valerie offers us a road map compass that helps us to reach new layers of dialogue. And this allows us to see beyond the hurt to a new level of forgiveness and compassion. Many members of the Sikh community were targeted in the days immediately following the attacks of 9/11. In the book, Kaur talks about the loss of her uncle, a member of the Sikh community. He was killed the day after 9/11. Why? Maybe because they looked different, maybe because they wore turbans, maybe because some people are racist, ignorant, or maybe even afraid. She writes about how the whole community came together to offer their prayers, sympathy, and support. She also writes in detail about the 2012 Oak Creek Massacre in Wisconsin. A lone gunman brutally attacked a Sikh Temple. Six people were killed, and 4 others severely injured. The motive for this was apparently white supremacy. Again, people from other religious communities, people from the area, from around the state and around the country came together to offer prayer and support. Ms. Kaur also talks frankly about the verbal, emotional, and sexual abuse that was inflicted upon her by some members of her family, a cousin, and a long-term fiancé. Despite all the hurt and harm, she is now a strong, whole, and loving person. In her book she challenges us ” to see no strangers by telling us to wonder about others, to grieve our hurts and fight through them. She challenges us to tend our wounds and the wounds of our opponents by paying attention to our rage, by listening and by reimaging what these relationships and the world might be. And then she challenges us to love ourselves. In order to love ourselves, we must learn how to breathe. Breathing is life-giving and creates space in our lives to think and see differently. Then we must learn to push through our grief, rage, and trauma. Having pushed through, we can find and transition to healing, forgiveness and even reconciliation”. A few weeks ago, our Metrowest Interfaith group was invited to a local Sikh Gurdwara to attend their worship service and participate in their Langar, a free community meal that is an important part of living out their faith. The meal is prepared and served by volunteers in the spirit of equality and hospitality. It was an amazing experience to witness their community and faith in action. Although I couldn’t understand all of the worship service; the music, movements, singing, chanting, and prayers were beautiful. The service evoked feelings of warmth, peace and well-being. One of the prayers was as follows: “I have forgotten my envy of others Since I found my sacred company. I see no enemy. I see no strangers. All of us belong to each other. What the divine does, I accept as good. I have received this wisdom from the holy. The One pervades all. Gazing upon the One, beholding the One, Nanak blossoms forth in happiness.” --Sri Guru Granth, Raag Kanarra There are 3 main beliefs of Sikhism: Remember God’s name with every breath; Work and earn by the sweat of the brow, live a family way of life and practice truthfulness and honesty in all dealings; and to share and live as an inspiration and support to the whole Community. As a person deeply interested in interfaith dialogue and relationships, the Sikh community has given me tools to make better changes in my life and to look beyond negativity and use Valerie’s compass as a way to make better connections and to look at and hear each other’s stories without judgement, and to make lasting systemic changes. Jess McGuire & Dianne Evans

On December 3, 2023, the Metrowest Interfaith Community and others gathered for a candlelight prayer and a shared meal together at Our Lady of Fatima Shrine in Holliston. Our Jewish and Muslim neighbors, Christian, Baha’i, Sikh, and others joined in as we brought together our sorrow and grief for so many uselessly killed, men, women, and children, of those still held captive, and so many others affected by this awful tragedy. From the Qur’an, teachings of the Baha’i, Christian, and Hebrew scriptures, from poetry, music, and reflection, we raised all our hopes for a peace that not only ceases violence but provides a future full of hope for everyone. Jess McGuire Recently, in the high holy days of our Jewish neighbors in town we were invited by Rabbi Mimi Micner to Temple Beth Torah’s celebration of Tashlich. For us Gentiles, that refers to casting away our sins of the past and with the new Jewish year, beginning with a clean slate and a pure heart. This is done ritually with prayer, song, the blowing of the shofar, and casting stones into a body of water, ridding ourselves of the burdens of the past year.

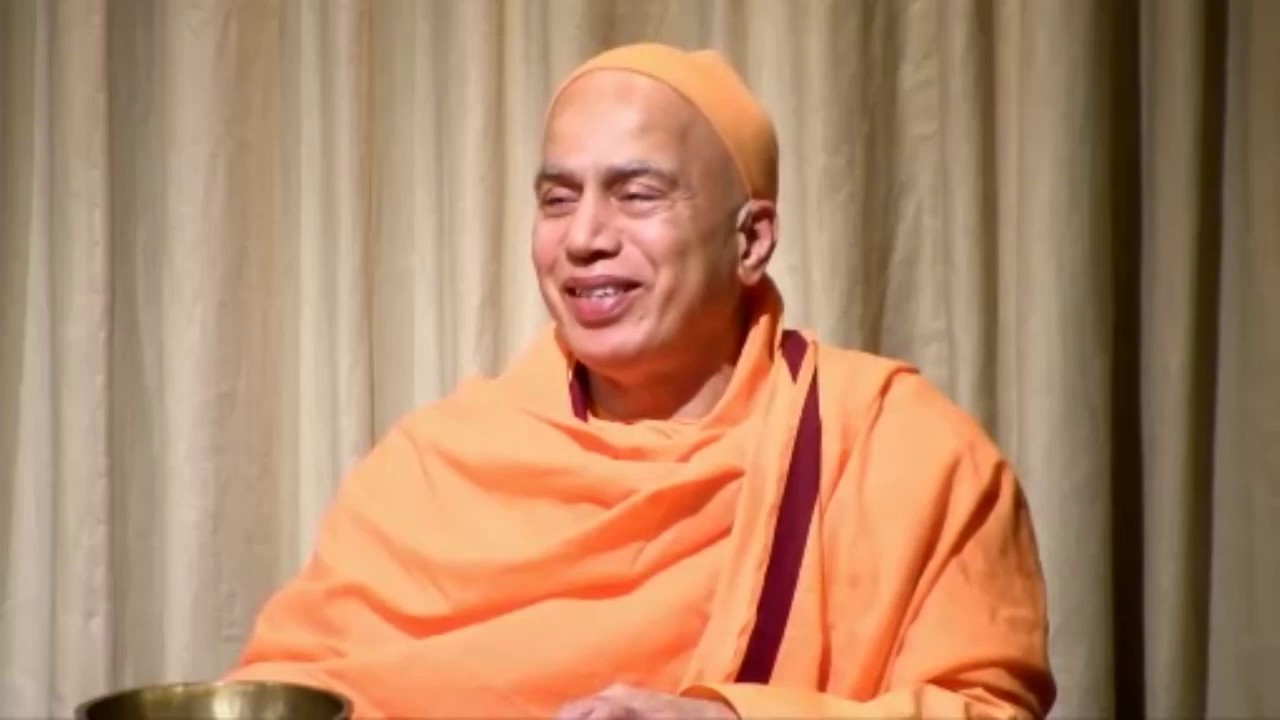

For me, it was one of the most spiritual experiences I ever had. My Catholic faith is often like a roller coaster with both highs and lows. My biggest battle is recovering from religious trauma and the conflicts I often feel with leadership in my own church. So, it makes sense to take the stones of burden I wish to release and let go, every stone is every hurt. As I did so Rabbi Mimi read a beautiful poem that seemed freeing to me as I cast my stones. It seemed powerful that it is possible to cast harm into deep water, that the ritual expresses a real possibility to be free of hurt, and the space it provides for something new, something hopeful. The stones sank deep into the Divine heart we all share. As a Catholic, I felt so close to Jewish friends who welcomed me, a stranger in their midst. Casting stones made me think of the possibilities peoples of all faiths hold in their hands. Casting Away We cast into the depths of the sea our sins And failures and regrets. Reflections of our imperfect selves flow away. What can we bear, With what can we bear to part? We upturn the darkness, bring what is buried to Light. What hurts still lodge, What wounds have yet to heal? We empty our hands, Release the remnants of shame, Let go fear and despair That have dug their home in us. Open hands, oping heart – The year flows out, the year flows in. (Marcia Falk)  Sri Ramakrishna’s cryptic phrase, “As many faiths, so many paths” (Bengali, যত মত, তত পথ) is often cited to affirm that all religions are true and valid paths to reach life’s ultimate goal. The word, মত, refers not specifically to “faith” but to “way of thinking” (which a “faith” generally provides). What Sri Ramakrishna was saying in effect is that every way of thinking is a pathway to understanding or to knowledge. This needs some qualification, of course. It is difficult to imagine every wayward and random thought leading to any sort of profound knowledge. Only the way of thinking that (1) is backed up by an authentic source (śruti), (2) does not contradict reason (yukti), and (3) can be verified by direct experience (anubhūti) becomes a pathway to knowledge. Affirming that all religions are valid paths does not imply that every religion is a unified single path. No religion is monolithic, that is, in no religion does everyone think alike or do things in the same way. Over the course of centuries, most of the world’s religions have developed varied ways of thinking within their own traditions, hence the presence of many sects, denominations and theologies; hence also robust debates and disagreements within every religious tradition. Every world religion is better imagined as a network of crisscrossing pathways which are distinct but never stray too far from one another—and may look like a single highway from 30,000 feet high. Although Vedanta is often spoken of in the singular, there are many different schools of thought within Vedanta, every one of which identifies itself as Vedanta. The three major divisions are nondualism (advaita), qualified nondualism (viśiṣṭādvaita), and dualism (dvaita). Every one of these has its own subdivisions. The more you dig, the more intricate and nuanced the variations become. What set apart these pathways in Vedanta are the differences among them, sometimes very subtle, in the way they conceive of the embodied self (jīva), the transcendent reality (brahman), and the world (jagat). The world phenomenon (saṁsāra, literally, “that which is constantly changing”) can be viewed through different lenses. Each view provides new insights and new ways to understand ourselves, the purpose of life, and how to achieve it. These different lenses are, in other words, frameworks for easy understanding. Each presents a worldview, a kind of window, through which we can look out at the canvas of life. It is possible to look at the world around and see it as a Cosmic Mystery (māyā) or as a Cosmic Person (virāṭ) or as a Cosmic Sacrifice (yajña) or as a Cosmic Union (yoga) or as a Cosmic Play (līlā)—at least five different windows through which to look out and make sense of what we see. Not all of these windows may resonate with everyone and they don’t have to. Perhaps one way of thinking may make more sense to someone than other ways of thinking about the same thing. Whichever of these ways rings true for me (and this can be quite subjective), it ends up becoming my worldview. It makes my life meaningful and purposeful. It is helpful to recognize that a different way of thinking may be equally meaningful to someone else. The ways of thinking are many, but what is thought of is one and the same. We are free to move from window to another, enjoying the gamut of views, but over time, we may find ourselves spending more time near one window and eventually moving our desk next to it—that window, then, becomes special for us, our personal favorite! It is important to keep in mind that each of these windows is only a means to understanding saṁsāra and the way to get out of it. As Sri Ramakrishna said: “God can be realized through all paths. All religions are true. The important thing is to reach the roof. You can reach it by stone stairs or by wooden stairs or by bamboo steps or by a rope. You can also climb up by a bamboo pole.” (Gospel, 111) Every way of reaching the roof is distinct but, no matter which way we choose, the end result is the same. In precisely the same way, each of the five “windows” that provides a way of thinking about the world is distinct, but no matter through which window we see, the end result is the same—namely, a framework that helps us understand the interrelationships between the individual, the world, and the divine reality that pervades and transcends them both. Every framework suggests practices, or the kind of “stairs,” which help us “reach the roof.” We cannot of course reach the roof if we insist on taking one step on the stone stairs, the next on the wooden stairs, and then on bamboo steps. That won’t work. The stairs are different and distinct. Hence we cannot combine concepts associated with one window with those in another, or search for ways to “reconcile” one with the other. These efforts serve no useful purpose. They only result in confusion and frustration. We cannot simultaneously look through two windows which are far apart. It’s not the windows that matter but the view they provide, the Truth they reveal. That Truth is one, no matter which window we look through. This article is from 2021 in the Holliston Reporter. Written by Susan Manning, it shares the work of the Metrowest Interfaith Dialogue Project in the community, and the extraordinary value to our interfaith relationships and solidarity. Twelve members of faith organizations in MetroWest, including Our Lady of Fatima Shrine in Holliston, work on a regular basis to make their communities more inclusive. They called it the MetroWest Interfaith Dialogue Project (MIDP).

According to Fr. Carl Chudy, Interfaith Outreach Coordinator for Our Lady of Fatima Shrine, recognizing the diversity in communities is important. “Our hope is to the honor the religious and nonreligious diversity of our communities and neighborhoods by creating an interfaith community within communities of different faiths. We focus on three goals: Foster opportunities to come together in order to come to know one another and the faiths that inspire us; Gain insight on how much we share in common through our faiths and values; Discover how interfaith dialogue and action can make a difference in our communities and neighborhoods and helps us all flourish together,” he said. So how did this group come together? Chudy said some of it had already been happening when the more formal project came together in 2017. “The MIDP began in 2017, building on interfaith and ecumenical activity already begun by Rev. Bonnie Steinroeder (First Congregational Church), Rev. Mark Peterson (Christ the King Lutheran Church), Rev. Sarah Robbins-Cole (St. Michael’s Episcopal Church), Rabbis Jennifer Rudin (Simcha-Services) and Moshe Givental (former Rabbi of Temple Beth Torah) and me, in various town activities. “My full-time work is Interfaith Outreach Coordinator for Our Lady of Fatima Shrine in Holliston, and I began enlisting others to join us in a wider interfaith approach, including Mynuddin Syed from the Islamic Community in Framingham, and Shaheen Akhtar from the Islamic Center of Boston in Wayland, in specific activities that attempts to invite Jewish, Christian, and Muslim neighbors to see how we can all flourish together,” he said. The present dialogue team covers a wider religious and nonreligious approach to interfaith dialogue and collaboration. They include Bert Cote (First Congregational Church), Rev. Mark Peterson (Christ the King Lutheran Church), Rev. Sarah Robbins-Cole (St. Michael Episcopal Church), Hussam Syed (Islamic Society of Framingham), Siri Karm Singh Khalsa (Sikh Community of Millis), Kristal Corona (Conflict Resolution Specialist), Chris Brumbach (Temple Beth Torah), Rabbi Jennifer Rudin (Simcha-Services), Rabbi Mimi Micner (Temple Beth Torah), Swami Tyagananda (Vedanta Society of Boston (Hindu)), Warren Chamberlain (Bahai Community) and Chudy. The groups hold various gatherings, although the pandemic put a wrench in the in-person events this past year. Chudy said the first event was a two-day interfaith event that began at Temple Beth Torah and finished at Our Lady of Fatima Shrine. It was themed: Loving and Listening: Honoring our Diversity as Multifaith Neighbors. “Providentially, our first encounter together at Temple Beth Torah was the very day of the shooting at the Tree of Life Synagogue in Pittsburgh, October 27, 2018, where an anti-Semitic attack killed eleven people and injured six,” said Chudy. The group has also held book reads in person and online on forgiveness and systemic racism, interfaith scripture studies, and special forums to look at issues of anti-Semitism and Islamophobia. “In light of shootings in mosques and synagogues elsewhere, we published declarations of solidarity, (found here: (www.hollistoninterfaith.org/building-bridges-blog/in-solidarity-with-our-muslim-neighbors-in-this-time-of-tragedy),” he said. Chudy said the division in this country is the exact reason the MIDP is needed. “These divided times impel us to act together based on our common ground as peoples of different faiths and those who are nonreligious. We also strive to explore our differences and the values that hold all of us accountable to each other,” he said. For more information, visit hollistoninterfaith.org or email [email protected]. Religious leaders and congregants from different faith communities around the MetroWest area formed in 2017 the Metrowest Interfaith Dialogue Project. We attempt to bring together members of our congregations and communities and the larger public in the interfaith dialogue of life, religious experience, justice, theology, and spirituality. As religious leaders and advocates, we seek to foster the truth of our oneness as a humanity, as well as provide space for holding our differences together with reverence. One way we do this is by bringing the power of our collective interfaith voice to bear on the issues facing the larger communities in which we serve. In December 2022 we began plans to gather volunteers from our different faith communities. They include our Muslim friends from Peace Islands Institute, The NEFAJ Islamic Center in Milford, Temple Beth Torah, The Vedanta Society of Boston (Hindu), Guru Ram Das Ashram and Gurdwara (Sikh), Baha'i, and our Protestant and Catholic neighbors. Since December 2012, 28 people from various religious communities and elsewhere joined us to help outfit apartments for incoming Ukrainian refugees in collaboration with Jewish Family Services, and to help create a new home for Ukrainians fleeing war. Susan Nolan, Rabbi Mimi Micner, and Fr. Carl Chudy of our interfaith network coordinates the committee and the work they do. Committee members offer their gifts and enthusiasm as we gathered to get to know one another and to begin to organize ourselves. We were not sure when the first family would come but hoped to build up a furniture and housewares inventory so we would be ready when they were able to arrive. A number of our members fundraised in their own religious communities, soliciting donations for gift cards, and other items. Other volunteered to pick up furniture and houseware donations, as well as purchase necessary items themselves. The enthusiasm of all was truly inspiring. As we worked to prepare ourselves, we waited for our first family to arrive. Finally, in April, we received news that a young couple, without children, would arrive in the beginning of May 2023. We had friends from the Muslim communities of Peace Islands Institute, St. Michael's Episcopal Church, Christ the King Lutheran Church, Our Lady of Family Shrine, St. Mary's Catholic Church, Temple Beth Torah, and the Baha'i community. We had youth from St. Michael's Episcopal Church come and clean some of the furniture we were storing for refugee families. Others came to hand pick what furniture would be taken to the new apartment, and another group who rented a U Haul truck and carry it to the apartment in Framingham. Through every step of the way, our liaison from Jewish Family Services, Sarah Leacu, would assist us with resources and the information we needed to do the work. Carrying in furniture, installing cable television for the first time, putting together the bed, gathering tables, lamps, and chairs. We had another group who did initial food shopping, providing sets of dishes and pots and pans, utensils and other items for the kitchen and bathroom.

On the evening of Monday, May 8, Juliia arrived from the airport, lost luggage and tired, to see her new home. Her case worker and others would continue to assist her with many things beyond that evening. But, for the first time, arriving at her new home, she came into the apartment overwhelmed and happy. She embraced both Susan and I and thanked us for all our friends did for her. Rabbi Mimi, made a delicious lasagna for her first meal in her home. Susan and I left that evening tired, happy, and talking of our next housing project for a new refugee family.  Interfaith literacy not only provides opportunities to learn of the depth of other faiths through our friendships, but also helps us to understand the extraordinary diversity within anyone of our religious traditions. Rabbi Mimi Micner, one of our dialogue partners from Temple Beth Torah, provided such a lesson to me. Prior to the start of Passover, she asked me to buy the temple's "chametz" in preparation of Passover. I said, "Sure, what's that?" Rabbi Mimi related that the Torah and Rabbinical teaching speak of the need to get rid of all foods that use grain, or suspected foods that do. On the holiday of Passover, the Torach says we are not to have any chametz in our possession (Exodus 12:19 and 13:7). Any food that is made out of grain that has been allowed to rise (ferment) is chametz. Common chametz items include bread, cakes, breakfast cereals, pastas, many liquors and more. This also applies to chametz that is locked up and out of sight. The Talmud, commenting on the Torah, begins a conversation about the laws around removing chametz from one's home and from there, the medieval-era drafters of Jewish law took the conversation of the Talmud and ruled that Jews would be able to remove chametz from their home through selling their chametz to people who are not Jewish and then get it back at the end of the holiday. Close to the eve of Passover, Rabbi Mimi and I met and read together a formal agreement for the selling of chametz. In this agreement, I not only agreed to buy her chametz, but Rabbi Mimi has the authority to sell on a special list, Harsha'ah, the chametz of others. In the ritual of the signing of this agreement, it is sealed not only with signatures, but also by means of kinyan sudar, by means of a handshake and the ritual lifting of the pen together that we both use to sign the document. Here our agreement is binding until her return also through the purchase price of one dollar, by way of Vemno of course. What seems like simple rituals for Passover, is something that connects Jews to their past and the Word of God that binds them together. As a Catholic priest, we are indebted to our Jewish neighbors and the gift of Judaism that is at the heart of so much of what we Christians treasure. The late Pope John Paul II once called our Jewish friends, our "elder brothers and sisters in faith." he author, Dorothy Buck is the USA coordinator for the Badilya Prayer Movement. Badaliya is an Arabic word that means to take the place of or substitute for another. It is a spiritual term that lies at the heart of the Christian faith experience and refers to the mystery of the image of God as Jesus sacrificing his life for all of humanity. To be a follower of Christ is to offer oneself out of love for the well-being of others. Louis Massignon and Mary Kahil established the Badaliya prayer group in Cairo in 1934. At that time Christians in Egypt were increasingly marginalized as Islam became the dominant religion in the region. The Badaliya was a way to open themselves to befriending and praying with and for their Muslim neighbors. It embraced Massignon’s own understanding that by learning the language and experiencing the traditions and culture of those of other religions our own faith life is enhanced. The Badaliya prayer was a testimony to the universal love of Christ. A Badaliya prayer group formed in Paris joining the one in Cairo, and eventually Badaliya prayer groups arose in many other cities around the world. They met monthly and many individual lay persons and members of religious communities joined this prayer movement in spirit as well. For more information, see the article “A Model of Hope: Louis Massignon’s Badaliya”. In 2003 the Badaliya prayer movement was re-created in the United States. Letters are sent via email to members gathering in Boston and Washington, DC as well as a growing list of people praying in solidarity around the U.S. and in other countries. The following monthly letters include inspirational material for the prayer and invitations to the gatherings. Today Christians around the world celebrate Palm Sunday, often referred to as Passion Sunday. We are coming to the end of a six-week Lenten journey of prayer, fasting, and alms-giving that invited us to step into the ancient land of Galilee and journey with Jesus as his disciples on the way to Jerusalem. We have gone with Jesus into the desert, been tempted by our hunger, as he was after forty days of fasting, to turn the stones into bread, and listened to his response to the tempter, “Man does not live by bread alone, but by every word that proceeds from the mouth of God”. We have found ourselves atop a parapet of the Temple being challenged as Jesus as if he is indeed the Son of God, to throw ourselves down with him and trust the angels to prevent him from harm, to which he quotes the Book of Deuteronomy with “It is said, Thou shalt not tempt the Lord your God.” And finally we are there with him on the mountain overlooking “all the kingdoms of the world” that Jesus is promised if he bows down to this one called, Satan. We recognize that all-too-tempting desire for wealth and power over earthly kingdoms that has enticed so many to this day and we cling to Jesus’ response, “You shall worship the Lord your God, and Him only shall you serve.”

If we have taken the journey seriously, we have walked with Jesus throughout the villages in Galilee and witnessed the healing power of Divine Love healing the deaf, the blind, the lepers, and welcoming the outcasts, the prostitutes, and tax collectors. We have even gone with Peter, James, and John up Mt. Tabor and experienced a glimpse of a transfigured Jesus conversing with Moses and Elijah only to redescend into the desert to continue the journey to Jerusalem, hardly willing to hear the many times he warns us that the Son of Man will be arrested by the Scribes and Pharisees, turned over to the Roman authorities, condemned and scourged and crucified as a common criminal. On this Palm Sunday, we wave our palms with the crowds as they shout hosannas around this popular Rabbi/teacher called Jesus as he descends from the Mount of Olives into Jerusalem mounted on a lowly beast of burden to celebrate the Feast of Passover with his disciples. And we hear with fear and trembling the story of what lies ahead in this week we call Holy. This year, in the midst of this spiritual and physical journey for those of us, baptized into the Life of Christ, our Muslim friends have begun their own spiritual journey of Ramadan. As in our Christian six weeks of Lent, the Ramadan fast and dedication to prayer and almsgiving has many lessons for Muslim believers. The self-discipline required to get through a month of fasting from sunrise to sunset every day is challenging yet carries within it vital life lessons. Meant to be undertaken in order to focus our attention on Allah, God alone, fasting and feeling hunger and thirst is a means to overcoming the habits that enslave us rather than experiencing ourselves as first and foremost believers in Allah. At the same time, it reminds us of those who fast out of no choice of their own due to poverty, displacement due to war and violence or devastating natural events like the earthquakes in Turkey and Syria leaving millions homeless. Out of fasting comes compassion and empathy for those in need which leads to charity, kindness, and generosity. It was in Medina, in the second year of the Hijrah, the migration of the followers of the Prophet to Medina from Mecca, that the Ramadan fast and the struggle to overcome the many temptations that can lead us astray as humans were established. The struggle against temptations to evil in ourselves, in our society and in the world is called Jihad. Through daily prayers and reading and reflecting on passages from the Qur’an, our devotional life is renewed and deepened. It was in this month that while fasting and praying the Prophet Muhammad received the first revelation that became the Qur’an. Both fasting and prayer are a means to open one’s heart to the ability to hear the holy words of God and allow them to shape how we live our lives individually and in the community. Identifying with the larger worldwide Muslim community, called the Ummah, strengthens our faith and the values of goodness, moral life, and a deeper sense of the Divine in our lives and in the world. Zakat is the word for almsgiving. The sharing of the breaking of the fast, or Iftar, with friends and family every evening is community building as well as an offering of help to those in need. Dr. Muzammil H. Siddiqi summarizes the moral and spiritual gifts of Ramadan as “Taqwa, the sum total of Islamic life. It is the highest of all virtues in the Islamic scheme of things. It means God-consciousness, piety, fear and awe of Allah and total commitment to all that is good and rejection of all that is evil and bad.” Ramadan is not only a time for fasting and struggle but is also a time of thanksgiving to the Creator and Sustainer of the universe for the gift of life, and all of creation. The lessons of Lent have led Christians into this Holy Week to experience the dramatic events that have taught thousands of years of Christians about how power structures are threatened by the prophetic voices calling for transformation, social justice, all-inclusive love, and equity and have sacrificed their lives that others may live. By fully experiencing this Holy Week, and by our Muslim friends fully experiencing this month of Ramadan, both faith communities will also learn that Divine Love always has the last word. References: Fasting in Ramadan: Lessons & Moralities by Dr. Muzammil H. Siddiqi Islamonline.net For all past letters to the Badaliya and Peace Islands See www.dcbuck.com January 18-25, 2023, is the yearly celebration and awareness-building opportunity of The Week of Christian Unity. The World Council of Churches and the Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity Joint Commission on the Week of Prayer for Christian Unity have shared with Graymoor the Scriptural Theme for the Week of Prayer for Christian Unity 2023. The theme is from Isaiah 1:17, “Do good; seek justice.” The entire scriptural passage for the theme is Isaiah 1:12-18, lamenting a lack of justice among the People of God. Yet, it also promises redemption by encouraging acts of justice.

Reverend Bonnie Steinroeder is a dear friend and dialogue partner with whom we have worked together for some years. She graciously accepted to share her own tradition and insight into the crucial work of ecumenism. On June 25, 1957, in Cleveland, Ohio, the Evangelical and Reformed Church, committed to “liberty of conscience inherent in the Gospel,” and the Congregational Christian Churches, a fellowship of biblical people under a mutual covenant for responsible freedom in Christ, joined together as the United Church of Christ (UCC). Since its inception, the UCC has sought to bring together those who wish to accept the joy and cost of discipleship with an emphasis on social justice and God’s extravagant welcome for all. The motto of the UCC is taken from John 17, “that they may all be one” which reflects the church’s desire to seek out common ground among all Christians. The UCC is non-creedal and congregational in polity. This means that each congregation decides for itself how it will operate and that there is no appointed authority figure who can mandate what any congregation must do or believe. The UCC is, however, bound in the covenant. Members of a congregation live in covenant to care for and help one another and congregations within the UCC belong to an association of churches that hold one another accountable in matters of faith. In practice, the openness of the UCC lends itself to an inclusive model for Christian unity. Because there is no doctrine that one must adhere to in order to join, one will find a wide range of beliefs among church members. As the pastor of a UCC congregation in Massachusetts, I am often asked how this diversity of beliefs functions within the denomination. Is it truly the case that any belief is accepted and does this promote unity or division? In my own church, I find that unity is best achieved when there is mutual respect for differing views. We are tied together through the love of Jesus but there is freedom for each person to interpret this ancient faith and the responsibility to make faith relevant for living in today’s world. This does not mean that there is never disagreement, but we strive to find consensus in the midst of disagreement in order to be faithful to our mutual covenant with God and one another. The United Church of Christ is a relatively young denomination. It’s roots are ecumenical and that can very much be seen in the makeup of our congregations today. Our members come from many faith traditions and in general, are attracted to the liberal theology and welcoming nature of our churches. For us, Christian unity does mean that we all need to think alike but rather live out the commandment of Jesus to love our neighbor as ourselves and to recognize and affirm all as beloved Children of God. Check out resources for this inspiring week at Greymoore Ecumenical and Interreligious Institute. |

AuthorFr. Carl Chudy Archives

June 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed